If you liked school, you’ll love work. The cruel, absurd abuses of power, the self-satisfied authority that the teachers and principals lorded over you, the intimidation and ridicule of your classmates don’t end at graduation. Those things are all present in the adult world, only more so. If you thought you lacked freedom before, wait until you have to answer to shift leaders, managers, owners, landlords, creditors, tax collectors, city councils, draft boards, law courts, and police. When you get out of school you may escape the jurisdiction of some authorities, but you enter the control of even more domineering ones. Do you enjoy being controlled by others who don’t understand or care about your wants and needs? Do you get anything out of obeying the instructions of employers, the restrictions of landlords, the laws of magistrates, people who have powers over you that you would never have given them willingly?

How is it that they get all this power? The answer is hierarchy.

Hierarchy is a value system in which your worth measured by the number of people and things you control, and how well you obey those above you. Weight is exerted downward through the power structure: everyone is forced to accept and conform to this system by everyone else. You’re afraid to disobey those above you because they can bring to bear against you the power of everyone and everything under them. You’re afraid to abdicate your power over those below you because they might end up above you. In our hierarchical system, we’re all so busy trying to protect ourselves from each other that we never have a chance to stop and think if this is really the best way our society could be organized. If we could think about it, we’d probably agree that it isn’t; for we all know happiness comes from control over our own lives, not other people’s lives. And as long as we’re busy competing for control over others, we’re bound to be the victims of control ourselves. Even the ones at the very top of the ladder are controlled by their position: they have to work around the clock to maintain it. One false move, and they could end up at the bottom.

It is our hierarchical system that teaches us from childhood to accept the power of any authority figure, regardless of whether it is in our best interest or not. We learn to bow instinctively before anyone who claims to be more important than we are. It is hierarchy that makes homophobia common among poor people in the U.S.A. — they’re desperate to feel more valuable, more significant than somebody. It is hierarchy at work when two hundred hardcore kids go to a rock club (already a mistake, but that’s a subject for another article) to see a band, and for some stupid reason the club owner won’t let them perform: there are two hundred and six people at the club, two hundred and five of whom want the band to play, but they all accept the decision of the club owner just because he is older and owns the place (i.e. has more financial clout, and thus more legal clout). It is hierarchical values that are responsible for racism (“white people are better than black people”), classism (“rich people are better than poor people”), sexism (“men are better than women”), and a thousand other prejudices that are deeply ingrained in our society. It is hierarchy that makes rich people look at poor people as if they aren’t even human, and vice versa. It pits employer against employee, manager against worker, teacher against student, making people struggle against each other rather than work together to help each other; separated this way, they can’t benefit from each other’s skills and ideas and abilities, but must live in jealousy and fear of them. It is hierarchy at work when your boss insults you or makes sexual advances at you and you can’t do anything about it, just as it is when police flaunt their power over you. For power does make people cruel and heartless, and submission does make people cowardly and stupid: and most people in a hierarchical system partake in both. Hierarchical values are responsible for our destruction of the natural environment and the exploitation of animals: led by the capitalist West, our species seeks control over anything we can get our claws on, at any cost to ourselves or others. And it is hierarchical values that send us to war, fighting for power over each other, inventing more and more powerful weapons until finally the whole world teeters on the edge of nuclear annihilation.

But what can we do about hierarchy? Isn’t that just the way the world works? Or are there other ways that people could interact, other values we could live by?

Hierarchy …

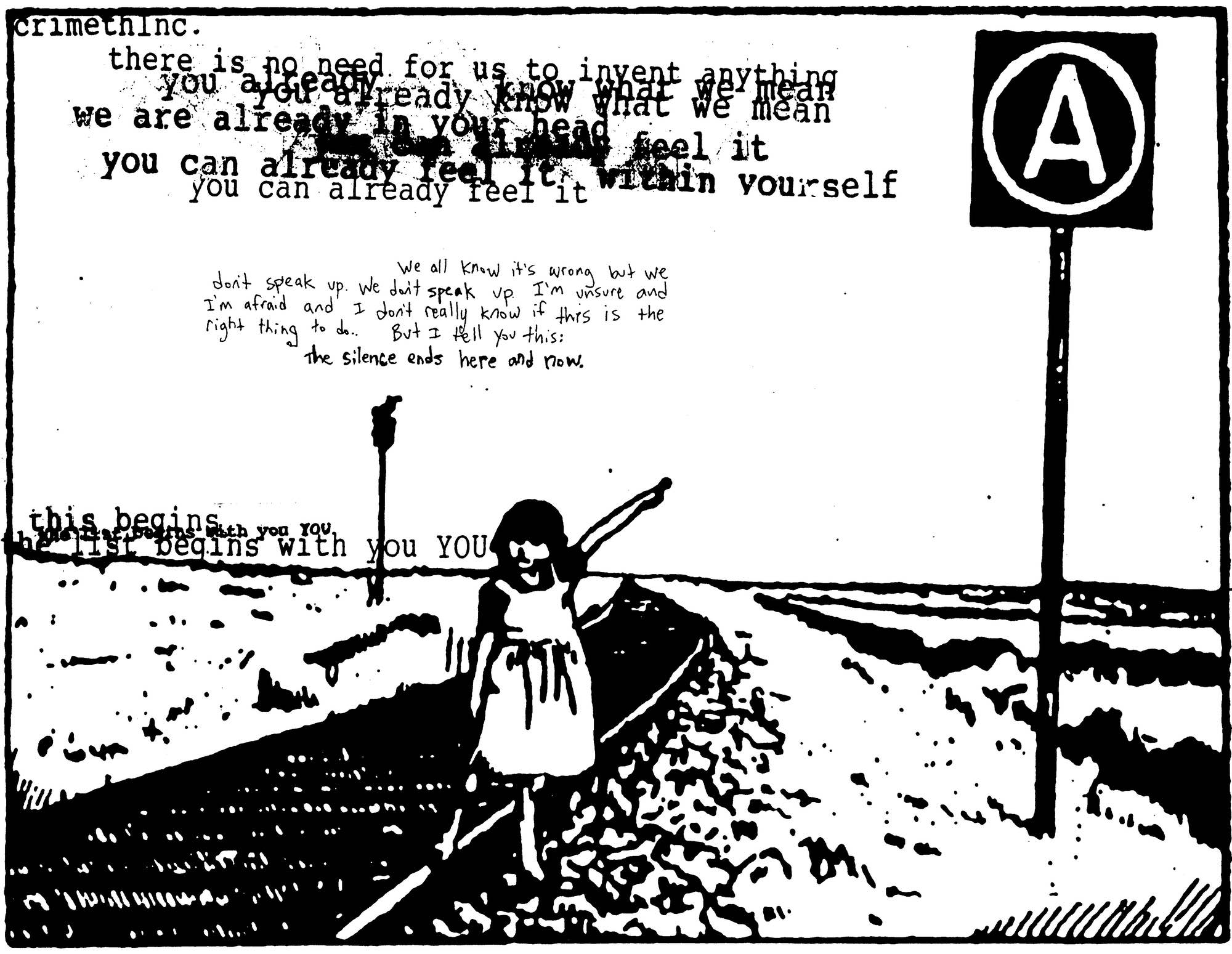

… and Anarchy

Hierarchy … and Anarchy

Resurrecting anarchism as a personal approach to life.

Stop thinking of anarchism as just another “world order,” just another social system. From where we all stand, in this very dominated, very controlled world, it is impossible to imagine living without any authorities, without laws or governments. No wonder anarchism isn’t usually taken seriously as a large-scale political or social program: no one can imagine what it would really be like, let alone how to achieve it — not even the anarchists themselves.

Instead, think of anarchism as an individual orientation to yourself and others, as a personal approach to life. That isn’t impossible to imagine. Conceived in these terms, what would anarchism be? It would be a decision to think for yourself rather than following blindly. It would be a rejection of hierarchy, a refusal to accept the “god given” authority of any nation, law, or other force as being more significant than your own authority over yourself. It would be an instinctive distrust of those who claim to have some sort of rank or status above the others around them, and an unwillingness to claim such status over others for yourself. Most of all, it would be a refusal to place responsibility for yourself in the hands of others: it would be the demand that each of us be able to choose our own destiny.

According to this definition, there are a great deal more anarchists than it seemed, though most wouldn’t refer to themselves as such. For most people, when they think about it, want to have the right to live their own lives, to think and act as they see fit. Most people trust themselves to figure out what they should do more than they trust any authority to dictate it to them. Almost everyone is frustrated when they find themselves pushing against faceless, impersonal power.

You don’t want to be at the mercy of governments, bureaucracies, police, or other outside forces, do you? Surely you don’t let them dictate your entire life. Don’t you do what you want to, what you believe in, at least whenever you can get away with it? In our everyday lives, we all are anarchists. Whenever we make decisions for ourselves, whenever we take responsibility for our own actions rather than deferring to some higher power, we are putting anarchism into practice. So if we are all anarchists by nature, why do we always end up accepting the domination of others, even creating forces to rule over us? Wouldn’t you rather figure out how to coexist with your fellow human beings by working it out directly between yourselves, rather than depending on some external set of rules? Remember, the system they accept is the one you must live under: if you want your freedom, you can’t afford to not be concerned about whether those around you demand control of their lives or not.

Do we really need masters to command and control us? In the West, for thousands of years, we have been sold centralized state power and hierarchy in general on the premise that we do. We’ve all been taught that without police, we would all kill each other; that without bosses, no work would ever get done; that without governments, civilization itself would fall to pieces. Is all this true? Certainly, it’s true that today little work gets done when the boss isn’t watching, chaos ensues when governments fall, and violence sometimes occurs when the police aren’t around. But are these really indications that there is no other way we could organize society? Isn’t it possible that workers won’t get anything done unless they are under observation because they are used to not doing anything without being prodded — more than that, because they resent being inspected, instructed, condescended to by their managers, and don’t want to do anything for them that they don’t have to? Perhaps if they were working together for a common goal, rather than being paid to take orders, working towards objectives that they have no say in and that don’t interest them much, they would be more proactive. Not to say that everyone is ready or able to do such a thing today; but our laziness is conditioned rather than natural, and in a different environment, we might find that people don’t need bosses to get things done. And as for police being necessary to maintain the peace: we won’t discuss the ways in which the role of “law enforcer” brings out the most brutal aspects of human beings, and how police brutality doesn’t exactly contribute to peace. How about the effects on civilians living in a police-protected state? Once the police are no longer a direct manifestation of the desires of the community they serve (and that happens quickly, whenever a police force is established: they become a force external to the rest of society, an outside authority), they are a force acting coercively on the people of that society. Violence isn’t just limited to physical harm: any relationship that is established by force, such as the one between police and civilians, is a violent relationship. When you are acted upon violently, you learn to act violently back. Isn’t it possible, then, that the implicit threat of police on every street corner — of the near omnipresence of uniformed, impersonal representatives of state power — contributes to tension and violence, rather than dispelling them? If that doesn’t seem likely to you, and you are middle class and/or white, ask a poor black or Hispanic man how the presence of police makes him feel. When the standard forms of human interaction all revolve around hierarchical power, when human intercourse so often comes down to giving and receiving orders (at work, at school, in the family, in legal courts), how can we expect to have no violence in our system? People are used to using force against each other in their daily lives, the force of authoritarian power; of course using physical force cannot be far behind in such a system. Perhaps if we were more used to treating each other as equals, to creating relationships based upon equal concern for each other’s needs, we wouldn’t see so many people resort to physical violence against each other. And what about government control? Without it, would our society fall into pieces, and our lives with it? Certainly, things would be a great deal different without governments than they are now — but is that necessarily a bad thing? Is our modern society really the best of all possible worlds? Is it worth it to grant masters and rulers so much control over our lives, out of fear of trying anything different? Besides, we can’t claim that we need government control to prevent mass bloodshed, because it is governments that have perpetrated the greatest slaughters of all: in wars, in holocausts, in the centrally organized enslaving and obliteration of entire peoples and cultures. And it may be that when governments break down, many people lose their lives in the resulting chaos and infighting. But this fighting is almost always between other power-hungry hierarchical groups, other would-be governors and rulers. If we were to reject hierarchy absolutely, and refuse to serve any force above ourselves, there would no longer be any large scale wars or holocausts. That would be a responsibility each of us would have to take on equally, to collectively refuse to recognize any power as worth serving, to swear allegiance to nothing but ourselves and our fellow human beings. But if we all were to do it, we would never see another world war again.

Of course, even if a world entirely without hierarchy is possible, we should not have any illusions that any of us will live to see it realized. That should not even be our concern: for it is foolish to arrange your life so that it revolves around something that you will never be able to experience. We should, rather, recognize the patterns of submission and domination in our own lives, and, to the best of our ability, break free of them. We should put the anarchist ideal (no masters, no slaves) into effect in our daily lives however we can. Every time one of us remembers not to accept the authority of the powers that be at face value, each time one of us is able to escape the system of domination for a moment (whether it is by getting away with something forbidden by a teacher or boss, relating to a member of a different social stratum as an equal, etc.), that is a victory for the individual and a blow against hierarchy.

Do you still believe that a hierarchy-free society is impossible? There are plenty of examples throughout human history: the bushmen of the Kalahari desert still live together without authorities, never trying to force or command each other to do things, but working together and granting each other freedom and autonomy. Sure, their society is being destroyed by our more warlike one — but that isn’t to say that an egalitarian society could not exist that was extremely hostile to, and well-defended against, the encroachments of external power! William Burroughs writes about an anarchist pirates’ stronghold a hundred years ago that was just that.

If you need an example closer to your daily life, remember the last time you gathered with your friends to relax on a Friday night. Some of you brought food, some of you brought entertainment, some provided other things, but nobody kept track of who owed what to whom. You did things as a group and enjoyed yourselves; things actually got done, but nobody was forced to do anything, and nobody assumed the position of chief. We have these moments of non-capitalist, non-coercive, non-hierarchical interaction in our lives constantly, and these are the times when we most enjoy the company of others, when we get the most out of other people; but somehow it doesn’t occur to us to demand that our society work this way, as well as our friendships and love affairs. Sure, it’s a lofty goal to ask that it does — but let’s dare to reach for high goals, let’s not fucking settle for anything less than the best in our lives! Each of us only gets a few years on this planet to enjoy life; let’s try to work together to do it, rather than fighting amongst each other for miserable prizes like status and power.

“Anarchism” is the revolutionary idea that no one is more qualified than you are to decide what your life will be.

— It means trying to figure out how to work together to meet our individual needs, how to work with each other rather than “for” or against each other. And when this is impossible, it means preferring strife to submission and domination.

— It means not valuing any system or ideology above the people it purports to serve, not valuing anything theoretical above the real things in this world. It means being faithful to real human beings (and animals, etc.), fighting for ourselves and for each other, not out of “responsibility,” not for “causes” or other intangible concepts.

— It means not forcing your desires into a hierarchical order, either, but accepting and embracing all of them, accepting yourself. It means not trying to force the self to abide by any external laws, not trying to restrict your emotions to the predictable or the practical, not pushing your instincts and desires into boxes: for there is no cage large enough to accommodate the human soul in all its flights, all its heights and depths.

— It means refusing to put the responsibility for your happiness in anyone else’s hands, whether that be parents, lovers, employers, or society itself. It means taking the pursuit of meaning and joy in your life upon your own shoulders.

For what else should we pursue, if not happiness? If something isn’t valuable because we find meaning and joy in it, then what could possibly make it important? How could abstractions like “responsibility,” “order,” or “propriety” possibly be more important than the real needs of the people who invented them? Should we serve employers, parents, the State, God, capitalism, moral law before ourselves? Who was it that taught you we should, anyway?