Once, flipping through a book on child psychology, I came across a chapter about adolescent rebellion. It suggested that in the first phase of a child’s youthful rebellion against her parents, she may attempt to distinguish herself from them by accusing them of not living up to their own values. For example, if they taught her that kindness and consideration are important, she will accuse them of not being compassionate enough. In this case the child has not yet defined herself or her own values; she still accepts the values and ideas that her parents passed on to her, and she is only able to assert her identity inside of that framework. It is only later, when she questions the very beliefs and morals that were presented to her as gospel, that she can become a free-standing individual.

I often think that we have not gotten beyond that first stage of rebellion in the hardcore scene. We criticize the actions of those in the mainstream and the effects of their society upon people and animals, we attack the ignorance and cruelty of their system, but we rarely stop to question the nature of what we all accept as “morality.” Could it be that this “morality,” by which we think we can judge their actions, is itself something that should be criticized? When we claim that the exploitation of animals is “morally wrong,” what does that mean? Are we perhaps just accepting their values and turning these values against them, rather than creating moral standards of our own?

Maybe right now you’re saying to yourself “what do you mean, create moral standards of our own? Something is either morally right or it isn’t—morality isn’t something you can make up, it’s not a matter of mere opinion.” Right there, you’re accepting one of the most basic tenets of the society that raised you: that right and wrong are not individual valuations, but fundamental laws of the world. This idea, a holdover from a deceased Christianity, is at the center of our civilization. If you are going to question the establishment, you should question it first!

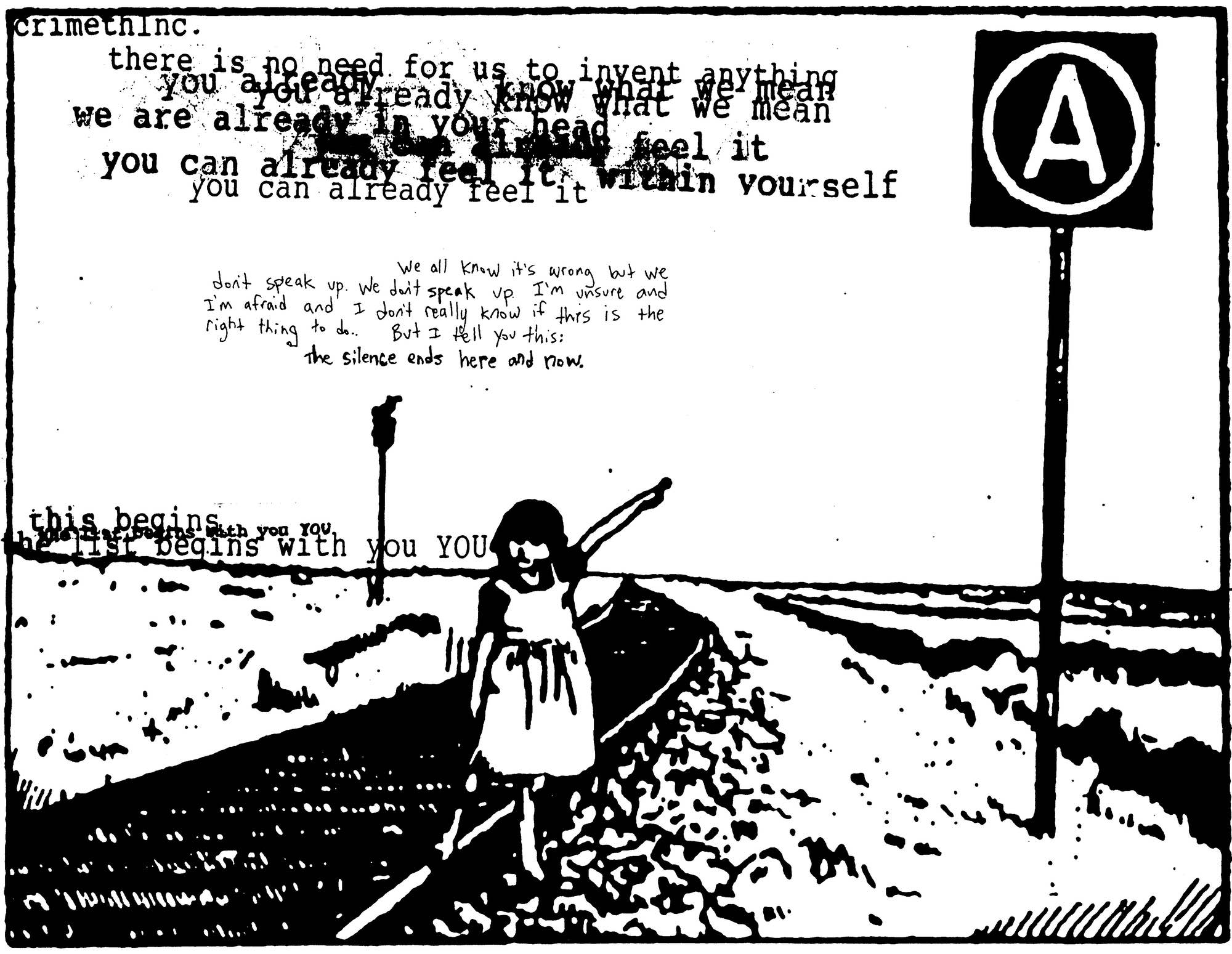

There is no such thing as good or evil

There is no universal right or wrong

There is only you…

and the values you choose for yourself.

Where does the idea of “Moral Law” come from?

Once upon a time, almost everyone believed in the existence of God. This God ruled over the world, He had absolute power over everything in it; and He had set down laws which all human beings had to obey. If they did not, they would suffer the most terrible of punishments at His hands. Naturally, most people obeyed the laws as well as they could, their fear of eternal suffering being stronger than their desire for anything forbidden. Because everyone lived according to the same laws, they could agree upon what “morality” was: it was the set of values decreed by God’s laws. Thus, good and evil, right and wrong, were decided by the authority of God, which everyone accepted out of fear.

One day, people began to wake up and realize that there was no such thing as God after all. There was no scientific evidence to demonstrate his existence, and few people could see any point in having faith in the irrational any longer. God pretty much disappeared from the world; nobody feared him or his punishments anymore.

But a strange thing happened. Though these people had the courage to question God’s existence, and even deny it to the ones who still believed in it, they didn’t dare to question the morality that His laws had mandated. Perhaps it just didn’t occur to them; everyone had been raised to hold the same beliefs about what was moral, and had come to speak about right and wrong in the same way, so maybe they just assumed it was obvious what was good and what was evil whether God was there to enforce it or not. Or perhaps people had become to used to living under these laws that they were afraid to even consider the possibility that the laws didn’t exist any more than God did.

This left humanity in an unusual position: though there was no longer an authority to decree certain things absolutely right or wrong, they still accepted the idea that some things were right or wrong by nature. Though they no longer had faith in a deity, they still had faith in a universal moral code that everyone had to follow. Though they no longer believed in God, they were not yet courageous enough to stop obeying His orders; they had abolished the idea of a divine ruler, but not the divinity of His code of ethics. This unquestioning submission to the laws of a long-departed heavenly master has been a long nightmare from which the human race is only just now beginning to awaken.

God is dead—and with him, Moral law

Without God, there is no longer any objective standard by which to judge good and evil. This realization was very troubling to philosophers a few decades ago, but it hasn’t really had much of an effect in other circles. Most people still seem to think that a universal morality can be grounded in something other than God’s laws: in what is good for people, in what is good for society, in what we feel called upon to do. But explanations of why these standards necessarily constitute “universal moral law” are hard to come by. Usually, the arguments for the existence of moral law are emotional rather than rational: “But don’t you think rape is wrong?” moralists ask, as if a shared opinion were a proof of universal truth. “But don’t you think people need to believe in something greater than themselves?” they appeal, as if needing to believe in something can make it true. Occasionally, they even resort to threats: “but what would happen if everyone decided that there is no good or evil? Wouldn’t we all kill each other?”

The real problem with the idea of universal moral law is that it asserts the existence of something that we have no way to know anything about. Believers in good and evil would have us believe that there are “moral truths”—that is, there are things that are morally true of this world, in the same way that it is true that the sky is blue. They claim that it is true of this world that murder is morally wrong just as it is true that water freezes at thirty two degrees. But we can investigate the freezing temperature of water scientifically: we can measure it and agree together that we have arrived at some kind of objective truth [that is, insofar as it is possible to speak of objective truth, for you postmodernist motherfuckers!]. On the other hand, what do we observe if we want to investigate whether it is true that murder is evil? There is no tablet of moral law on a mountaintop for us to consult, there are no commandments carved into the sky above us; all we have to go on are our own instincts and the words of a bunch of priests and other self-appointed moral experts, many of whom don’t even agree. As for the words of the priests and moralists, if they can’t offer any hard evidence from this world, why should we believe their claims? And regarding our instincts—if we feel that something is right or wrong, that may make it right or wrong for us, but that’s not proof that it is universally good or evil. Thus, the idea that there are universal moral laws is mere superstition: it is a claim that things exist in this world which we can never actually experience or learn anything about. And we would do well not to waste our time wondering about things we can never know anything about. When two people fundamentally disagree over what is right or wrong, there is no way to resolve the debate. There is nothing in this world to which they can refer to see which one is correct—because there really are no universal moral laws, just personal evaluations. So the only important question is where your values come from: do you create them yourself, according to your own desires, or do you accept them from someone else… someone else who has disguised their opinions as “universal truths”?

Haven’t you always been a little suspicious of the idea of universal moral truths, anyway? This world is filled with groups and individuals who want to convert you to their religions, their dogmas, their political agendas, their opinions. Of course they will tell you that one set of values is true for everybody, and of course they will tell you that their values are the correct ones. Once you’re convinced that there is only one standard of right and wrong, they’re only a step away from convincing you that their standard is the right one. How carefully we should approach those who would sell us the idea of “universal moral law,” then! Their claim that morality is a matter of universal law is probably just a sneaky way to get us to accept their values rather than forging our own, which might conflict with theirs.

So, to protect ourselves from the superstitions of the moralists and the trickery of the evangelists, let us be done with the idea of moral law. Let us step forward into a new era, in which we will make values of our own rather than accepting moral laws out of fear and obedience. Let this be our new creed: There is no universal moral code that should dictate human behavior. There is no such thing as good or evil, there is no universal standard of right and wrong. Our values and morals come from us and belong to us, whether we like it or not; so we should claim them proudly for ourselves, as our own creations, rather than seeking some external justification for them.

But if there’s no good or evil, if nothing has any intrinsic moral value, how do we know what to do?

Make your own good and evil. If there is no moral law standing over us, that means we’re free—free to do whatever we want, free to be whatever we want, free to pursue our desires without feeling any guilt or shame about them. Figure out what it is you want in your life, and go for it; create whatever values are right for you, and live by them. It won’t be easy, by any means; desires pull in different directions, they come and go without warning, so keeping up with them and choosing among them is a difficult task—of course obeying instructions is easier, less complicated. But if we just live our lives as we have been instructed to, the chances are very slim that we will get what we want out of life: each of us is different and has different needs, so how could one set of “moral truths” work for each of us? If we take responsibility for ourselves and each carve our own table of values, then we will have a fighting chance of attaining some measure of happiness. The old moral laws are left over from days when we lived in fearful submission to a nonexistent God, anyway; with their departure, we can rid ourselves of all the cowardice, submission, and superstition that has characterized our past.

Some misunderstand the claim that we should pursue our own desires to be mere hedonism. But it is not the fleeting, insubstantial desires of the typical libertine that we are speaking about here. It is the strongest, deepest, most lasting desires and inclinations of the individual: it is her most fundamental loves and hates that should shape her values. And the fact that there is no God to demand that we love one another or act virtuously does not mean that we should not do these things for our own sake, if we find them rewarding, which almost all of us do. But let us do what we do for our own sake, not out of obedience to some deity or moral code!

But how can we justify acting on our ethics, if we can’t base them on universal moral truths?

Morality has been something justified externally for so long that today we hardly know how to conceive of it in any other way. We have always had to claim that our values proceeded from something external to us, because basing values on our own desires was (not surprisingly!) branded evil by the preachers of moral law. Today we still feel instinctively that our actions must be justified by something outside of ourselves, something “greater” than ourselves—if not by God, then by moral law, state law, public opinion, justice, “love of man,” etc. We have been so conditioned by centuries of asking permission to feel things and do things, of being forbidden to base any decisions on our own needs, that we still want to think we are obeying some higher power even when we act on our own desires and beliefs; somehow, it seems more defensible to act out of submission to some kind of authority than in the service of our own inclinations. We feel so ashamed of our own aspirations and desires that we would rather attribute our actions to something “higher” than them. But what could be greater than our own desires, what could possibly provide better justification for our actions? Should we be serving something external without consulting our desires, perhaps even against our desires?

This question of justification is where so many hardcore bands have gone wrong. They attack what they see as injustice not on the grounds that they don’t want to see such things happen, but on the grounds that it is “morally wrong.” By doing so, they seek the support of everyone who still believes in the fable of moral law, and they get to see themselves as servants of the Truth. These hardcore bands should not be taking advantage of popular delusions to make their points, but should be challenging assumptions and questioning traditions in everything they do. An improvement in, for example, animal rights, which is achieved in the name of justice and morality, is a step forward at the cost of two steps back: it solves one problem while reproducing and reinforcing another. Certainly such improvements could be fought for and attained on the grounds that they are desirable (nobody who truly considered it would really want to needlessly slaughter and mistreat animals, would they?), rather than with tactics leftover from Christian superstition. Unfortunately, because of centuries of conditioning, it feels so good to feel justified by some “higher force,” to be obeying “moral law,” to be enforcing “justice” and fighting “evil” that these bands get caught up in their role as moral enforcers and forget to question whether the idea of moral law makes sense in the first place. There is a sensation of power that comes from believing that one is serving a higher authority, the same one that attracts people to fascism. It’s always tempting to paint any struggle as good against evil, right against wrong; but that is not just an oversimplification, it is a falsification: for no such things exist. We can act compassionately towards each other because we want to, not just because “morality dictates,” you know! We don’t need any justification from above to care about animals and humans, or to act to protect them. We need only to feel in our hearts that it is right, that it is right for us, to have all the reason we need. Thus we can justify acting on our ethics without basing them on moral truths simply by not being ashamed of our desires: by being proud enough of them to accept them for what they are, as the forces that drive us as individuals. And our own values might not be right for everyone, it’s true; but they are all each of us has to go on, so we should dare to act on them rather than wishing for some impossible greater justification.

But what would happen if everyone decided that there is no good or evil? Wouldn’t we all kill each other?

This question presupposes that people refrain from killing each other only because they have been taught that it is evil to do so. Is humanity really so absolutely bloodthirsty and vicious that we would all rape and kill each other if we weren’t restrained by superstition? It seems more likely to me that we desire to get along with each other at least as much as we desire to be destructive—don’t you usually enjoy helping others more than you enjoy hurting them? Today, most people claim to believe that compassion and fairness are morally right, but this has done little to make the world into a compassionate and fair place. Might it not be true that we would act upon our natural inclinations to human decency more, rather than less, if we did not feel that charity and justice were obligatory? What would it really be worth, anyway, if we did all fulfill our “duty” to be good to each other, if it was only because we were obeying moral imperatives? Wouldn’t it mean a lot more for us to treat each other with consideration because we want to, rather than because we feel required to?

And if the abolition of the myth of moral law somehow causes more strife between human beings, won’t that still be better than living as slaves to superstitions? If we make our own minds up about what our values are and how we will live according to them, we at least will have the chance to pursue our desires and perhaps enjoy life, even if we have to struggle against each other. But if we choose to live according to rules set for us by others, we sacrifice the chance to choose our destinies and pursue our dreams. No matter how smoothly we might get along in the shackles of moral law, is it worth the abdication of our self determination? I wouldn’t have the heart to lie to a fellow human being and tell him he had to conform to some ethical mandate whether it was in his best interest or not, even if that lie would prevent a conflict between us. Because I care about human beings, I want them to be free to do what is right for them. Isn’t that more important than mere peace on earth? Isn’t freedom, even dangerous freedom, preferable to the safest slavery, to peace bought with ignorance, cowardice, and submission?

Besides, look back at our history. So much bloodshed, deception, and oppression has already been perpetrated in the name of right and wrong. The bloodiest wars have been fought between opponents who each thought they were fighting on the side of moral truth. The idea of moral law doesn’t help us get along, it turns us against each other, to contend over whose moral law is the “true” one. There can be no real progress in human relations until everyone’s perspectives on ethics and values are acknowledged; then we can finally begin to work out our differences and learn to live together, without fighting over the absolutely stupid question of whose values and desires are “right.” For your own sake, for the sake of humanity, cast away the antiquated notions of good and evil and create your values for yourself!