Media transforms experience, memory, and communication into something synthetic and external. In a media-driven society, we depend on technology for access to these externalized aspects of ourselves. Books, recordings, movies, radio, television, internet, mobile phones: each of these successive innovations has penetrated deeper into daily life, mediating an ever greater proportion of our experience.

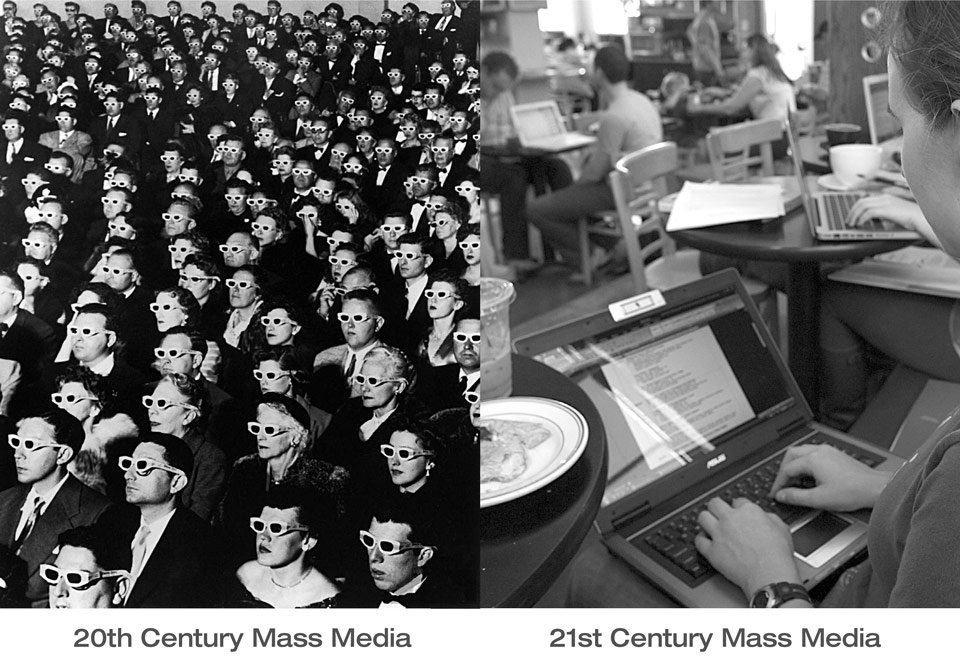

Until the end of the 20th century, mass media was essentially unidirectional, with information flowing one way and attention flowing the other. Critics generally focused on this aspect of its structure, charging that it gave a small cabal tremendous influence over society while immobilizing everyone else as spectators. In contrast, underground media championed more participatory and decentralized forms.

Participation and decentralization suddenly became mainstream with the arrival of widely accessible digital media. In many ways, the internet offered a liberating and empowering terrain for new modes of communication. Since the basic model was developed by researchers funded by the military rather than the private sector, it was designed to be useful rather than profitable. To this day, much of the internet remains a sort of Wild West in which it’s difficult to enforce traditional property laws. The ability to share content freely and directly among users has had a tremendous impact on several industries, while collaborative formats such as Wikipedia and open-source software show how easily people can meet their needs without private property. Corporations are still scrambling to figure out how to make money on the internet beyond online stores and advertising.

Yet as more and more of our lives become digitized, it’s important not to take it for granted that this is always for the best. Capitalism thrives by absorbing aspects of the world that were once free and then offering access to them at a price, and this price is not always exacted in dollars.

We should be especially attentive to the ways new media are convenient: convenience can be a sign that the infinite possibilities of human life are being forcibly narrowed down. Indeed, these innovations are barely even optional: nowadays it’s difficult to maintain friendships or get hired without a cell phone and an online profile. More and more of our mental processes and social lives must pass through the mediation of technologies that map our activities and relationships for corporations and government intelligence. These formats also shape the content of those activities and relationships.

The networks offered by Facebook aren’t new; what’s new is that they seem external to us. We’ve always had social networks, but no one could use them to sell advertisements—nor were they so easy to map. Now they reappear as something we have to consult. People corresponded with old friends, taught themselves skills, and heard about public events long before email, Google, and Twitter. Of course, these technologies are extremely helpful in a world in which few of us are close with our neighbors or spend more than a few years in any location. The forms assumed by technology and daily life influence each other, making it increasingly unthinkable to uncouple them.

As our need for and access to information increase beyond the scope of anything we could internalize, information seems to become separate from us. This is suspiciously similar to the forcible separation from the products of their labor that transformed workers into consumers. The information on the internet is not entirely free—computers and internet access cost money, not to mention the electrical and environmental costs of producing these and running servers all around the world. And what if corporations figure out how to charge us more for access to all these technologies once we’ve become totally dependent on them? If they can, not only power and knowledge but even the ability to maintain social ties will be directly contingent on wealth.

But this could be the wrong thing to watch out for. Old-money conglomerates may not be able to consolidate power in this new terrain after all. The ways capitalism colonizes our lives via digital technologies may not resemble the old forms of colonization.

Like any pyramid scheme, capitalism has to expand constantly, absorbing new resources and subjects. It already extends across the entire planet; the final war of colonization is being fought at the foot of the Himalayas, the very edge of the world. In theory, it should be about to collapse now that it has run out of horizons. But what if it could go on expanding into us, and these new technologies are like the Niña, Pinta, and Santa María landing on the continent of our own mental processes and social ties?

In this account, the internet functions as another successive layer of alienation built on the material economy. If a great deal of what is available on the internet is free of charge, this is not just because the process of colonization is not yet complete, but also because the determinant currency in the media is not dollars but attention. Attention functions in the information economy the same way control of material resources functions in the industrial economy. Even if attention doesn’t instantly translate into income online, it can help secure it offline. As currencies, attention and capital behave differently, but they both serve to create power imbalances.

What is capital, really? Once you strip away the superstitions that make it seem like a force of nature, it’s essentially a social construct that enables some people to amass power over others. Without the notion of private property, which is only “real” insofar as everyone abides by it, material resources couldn’t function as capital. In this regard, property rights serve the same purpose that the notion of divine right of kings used to: both form the foundation of systems assigning sovereignty. Some people believe passionately in property rights even as those rights are used to strip them of any influence in society. It could be said that these people are under the spell of property.

Similarly, when an advertising agent sets out to make a meme go viral, you could say she is trying to cast a spell. If attention is the currency of the media, gaining it is a way to cause people to buy literally and figuratively into a power structure. The determinant factor is not whether people agree with or approve of what they see, but to what extent it shapes their behavior.

Digital media appear to have decentralized attention, but they are also standardizing the venues through which it circulates. Beware entities that amass attention even if they never convert it into financial assets. The real power of Google and Facebook isn’t in their financial holdings but in the ways they structure the flow of information. In imposing a unitary logic on communication, relationships, and inquiry, they position themselves as the power brokers of the new era.

Behind these corporations stands the NSA, which now has unprecedented ability to map relationships and thought processes. Monitoring Google searches, it is possible to trace an internet user’s train of thought in real time. The NSA has even less need to convert internet use directly into financial gain; the currency it seeks is information itself, with which to direct the brute force of government. The role of the surveillance state is to maintain the conditions for corporations like Facebook to do business; the more power those corporations accumulate, financial or otherwise, the more power flows back into the hands of the government.

Until the Prism scandal, many people thought that surveillance and censorship were chiefly employed in places like Syria and Tunisia. In fact, most of the censorship technology those governments use comes from Silicon Valley—and was first applied right here in the US. Since even the slightest internet censorship presupposes effective and exhaustive surveillance, it is a small step from regulation to lockdown. The more we depend on digital technology, the more vulnerable we are to massive institutions against which we have very little leverage.

This isn’t a criticism of technology per se. The point is that it’s not neutral: technology is always shaped by the structures of the society in which it is developed and applied. Most of the technologies familiar to us were shaped by the imperatives of profit and rule, but a society based on other values would surely produce other technologies. As digital technology becomes increasingly enmeshed in the fabric of our society, the important question is not whether to use it, but how to undermine the structures that produced it.