Throughout the history of Western civilization the relationship of human beings to other animals has never been particularly “civil.” What was once an uneasy coexistence swiftly became a relationship of domination and exploitation as humankind became more organized and technologically developed. In recent years, animal rights activists have brought international attention to the treatment and living conditions of animals in factory farms, zoos, circuses, and laboratories, but a serious discussion has yet to begin about the lives of the animals that exist in an environment that strikes much closer to home–the lives of domesticated animals, of our own household pets. A consideration of the lives our pets must lead reveals that they too are exploited in their relationship with human beings; but more than that, it also reveals something to us about ourselves.

Certainly there are plenty of happy, well-adjusted domesticated animals who manage to lead lives that are, for them, exciting and fulfilling. Still, history shows us that human beings in the worst of conditions, even during such periods of suffering and abomination as the Holocaust, have often managed to enjoy life, to fall in love and forge friendships, to find meaning in their day to day existence; for human beings are durable and resilient, and like all animals will adapt as well as they can to survive and thrive in any situation. So the fact that many animals–or humans, for that matter–are happy in our homes is by no means adequate reason to set aside a consideration of the merits of domesticated life.

Let us consider the usual contents of the lives of today’s domesticated animals. Life begins, for most of them, in what we would refer to in human terms as a “broken home.” Young dogs and cats are routinely taken from the company of their mothers and siblings at an extremely early age and thrust into an alien environment, whether it be a crowded, chaotic pet shop or the home of their new owner. Many of them are mistreated and abused (it is not at all uncommon for a dog, house cat, or parrot to have a phobia of human males, for many of them are abused by men in their youth), and many more are orphaned. More often than not, when domesticated animals reproduce it is looked upon as an unplanned inconvenience by their human owners, and the unwanted offspring are treated accordingly. Consider how difficult it is for young men and women who grow up in “broken homes,” or in the adoption agency/youth reform program circuit, to become happy and self-confident, and it will become clear how difficult growing up must be for today’s domesticated animals.

But a difficult childhood is the only the beginning of a difficult and unnatural life for today’s typical house cat, gerbil, or parrot. For not only are the environments (i.e. cages, little glass boxes, six-room apartments and houses with climate control, and–at best–suburban back yards with the lawns mowed and bushes trimmed) which they must inhabit drastically different from those for which nature prepared them, but their role in the lives of the human beings who control their fate is itself unnatural. Most human beings who keep animals regard them as if they were, in some senses, toys rather than real animals. That seems like an unfair charge, but consider the usual relationship of these humans and animals, and the assumptions upon which the human owners keep these animals. Certainly these owners try to provide for the animals’ needs, and often offer affection, but the fundamental role these animals play in the homes and lives of these people is the role of entertainment (and, often, of surrogate family/friends as well). That is, the animals are kept by the human beings in the expectation that they will bring some sort of fun, and perhaps love, in their owners’ lives. Their role is not to be animals, that is, to hunt mice, to fly south for the winter, to chase down elk, to sharpen their claws where they please, to mark their territory with urine and court members of the opposite sex. Rather, they are expected to be modern court jesters or courtesans in the Western household.

The ramifications of this relationship between animals and humans are many, but we can see that this arrangement is not exactly in the best interest of the animals involved when we consider the “adjustments” human beings customarily make to their pets to make these pets fulfill their domestic roles more effectively. House cats are the most obvious example: their owners routinely declaw and sterilize them so they will better fulfill their role as polite toys, rather than real animals, in the home. Having and using claws is a pretty basic part of being a cat; a cat without claws is like a human being without fingers: it may get used to the situation, and even figure out how to enjoy life despite the alteration, but something will be missing from its life forever.

Similarly, though some say that sterilization is humane and makes life simpler for these animals, is this a simplification any of us would willingly choose for ourselves? Sterilization affects more than just the sex lives of animals; it changes their hormonal balance, changing their very personalities. A sterilized cat will often gain weight, slow down, become less spirited. Sterilized cats and dogs are easier for their owners to deal with in a number of ways, but this must come at a cost to their enjoyment of life itself. A frustrated female cat in heat may not seem to be enjoying life very much, but if you take away a being’s desires, what meaning is left for it to find in life? Left with its natural inclinations either surgically removed or frustrated by an environment much different than the one for which nature designed it, the sterilized cat will often become dull, grouchy, and fat–for eating the food its master provides is the only pleasure left to it.

Most of us can quickly call to mind an overweight, pathetic, neurotic dog or similarly maladjusted house pet that we have met at some time in our lives. These animals are the casualties of the exploitative relationship that exists today between humans and domesticated animals. Expected to be content as mere playthings, to eat standardized pet food that comes out of a box, and to live in quarters that are painfully cramped compared to their natural environments, it should come as no surprise that these animals are no longer as energetic or as passionate as wild animals. Once healthy and self-sufficient in their natural environment, these animals are now forced into humiliating dependence upon human beings who do not–cannot–permit them to live the lives that they would find fulfilling.

This is not to say that there is any truly viable alternative to domestication for these animals today. The “outside world” is no place for them to run wild or reproduce in; their natural habitats, for those animals who could still adapt back to them, have been changed beyond all recognition by pollution and other forces. The emerging new global environment, pockmarked by fields of asphalt, forests of steel, and cliffs of concrete, is only hospitable to pigeons and cockroaches. Compared to life in the “outside world,” domesticated life is a lesser of two evils for house cats and parakeets alike.

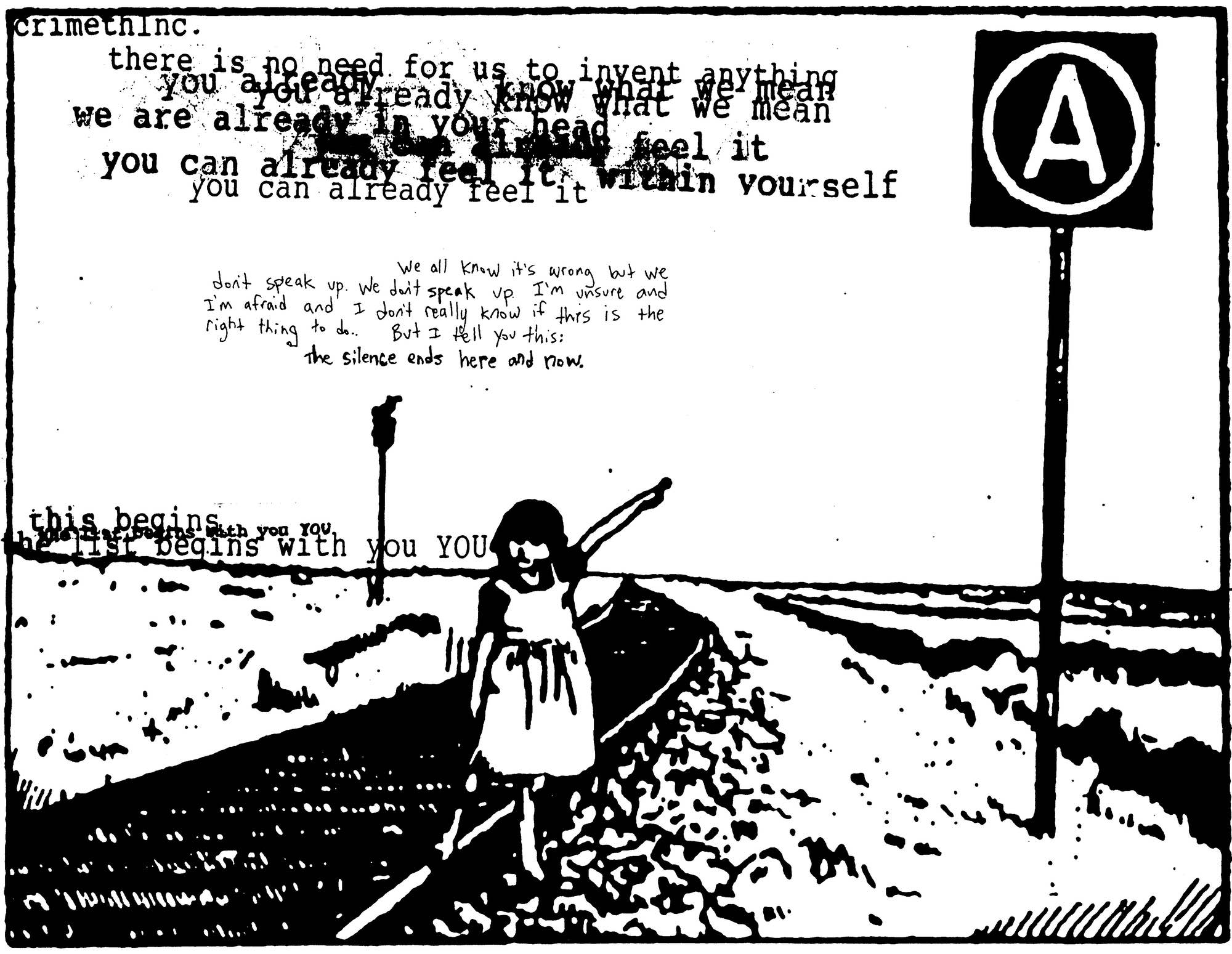

And this is what is most tragic about this situation: there is no way out of the technological, over-organized world we have created; no way out for animals or humans. For we are really not much different from the animals we keep in cages and fishtanks in our homes: We too live in small, climate-controlled boxes, called apartments. We too buy standardized food to eat at McDonalds, food much different from the food our ancestors had evolved to eat. We too can find no outlet for our spontaneous, “wild” urges, castrated and declawed as we are by the necessities of living in cramped cities and suburbs under cramping legal and cultural restrictions. We too cannot wander far from our kennels, leashed as we are by 9-to-5 jobs, by apartment leases, even by political boundaries. And if we did wander far, what would we find? Forests, jungles, wild plains, majestic canyons? These are swiftly disappearing as we work around the clock to wrap our world in a skin of concrete, to make sure that all the grass is watered by sprinklers and all the swamps are drained and surveyed to be turned into office space. And what we don’t transform into bigger cages and fishtanks for ourselves, we will surely make useless with pollution, if we do not reconsider and redirect our actions on a massive scale.

Perhaps we can learn about ourselves from the example of our own pets. We might do well to learn from them that real happiness does not follow from merely providing for food, physical health, and safety, but from much more complicated elements of life. The solution to the problem of the emotional poverty of domesticated life for animals, and for humans, is clearly not a simple one. We must begin by reevaluating what life should be for humans and animals alike, and what our society must be so that our lives can be meaningful and fulfilling. And we do not have too much time to waste; for already we have bred dogs that do not know how to survive without leashes, and soon there may not be any going back for us either.

“You [white folks] have not only altered and malformed your winged and four-legged cousins; you have done it to yourselves. You have changed men into chairmen of boards, into office workers, into time-clock punchers. You have changed your women into housewives, truly fearful creatures. I was once invited to the house of one. ‘Watch the ashes, don’t smoke, you’ll stain the curtains. Watch the goldfish bowl, don’t lean your head against the wallpaper; your hair may be greasy. Don’t spill liquor on that table: it has a delicate finish. You should have wiped your boots; the floor was just varnished. Don’t don’t don’t’ That is crazy. You live in prisons you have built for yourselves, calling them ‘homes, offices, factories.’“

-John (Fire) Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes, Lame Deer Seeker of Visions. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1994 [1972], 121.