Remember how differently time passed when you were twelve years old? One summer was a whole lifetime, and each day passed like a month does for you now. For everything was new: each day held experiences and emotions that you had never encountered before, and by the time that summer was over you had become a different person. Perhaps you felt a wild freedom then that has since deserted you: you felt as if anything could happen, as if your life could end up being virtually anything at all. Now, deeper into that life, it doesn’t seem so unpredictable. The things that were once new and transforming have long since lost their freshness and danger, and the future ahead of you seems to have already been determined by your past.

It is thus that each of us is dominated by history: the past lies upon us like a dead hand, guiding and controlling as if from the grave. At the same time as it gives the individual a conception of herself, an “identity,” it piles weight upon her that she must fight to shake off if she is to remain light and free enough to continue reinventing her life and herself. It is the same for the artist: even the most challenging innovations eventually become crutches and clichs. Once an artist has come up with one good solution for a creative problem, it is hard for her to break free of it to conceive of other possible solutions. That is why most great artists can only offer a few really revolutionary ideas: they become trapped by the very systems they create, just as these systems trap those who come after. It is hard to do something entirely new when one finds oneself up against a thousand years of painting history and tradition. And this is the same for the lover, for the mathematician and the adventurer: for all, the past is an adversary to action in the present, an ever-increasing force of inertia that must be overcome. It is the same for the radical, too. Conventional wisdom has it that a knowledge of the past is indispensable in the pursuit of freedom and social change. But today’s radical thinkers and activists are no closer to changing the world for their knowledge of past philosophies and struggles; on the contrary, they seem mired in ancient methods and arguments, unable to apprehend what is needed in the present to make things happen. Their place in the tradition of struggle has trapped them in a losing battle, defending positions long useless and outmoded; their constant references to the past not only render them incomprehensible to others, but also prevent them from referencing what is going on around them. Let’s consider what it is about history that makes it so paralyzing. In the case of world history, it is the exclusive, anti-subjective nature of the thing: History (with a capital “H”) is purportedly seen by the objective eye of science, as if “from above;” it demands that the individual value her impressions and experiences less than the official Truth about the past. But it is not just official history that paralyzes us, it is the very idea of the past itself. Try thinking of the world as including all past and future time as well as present space. An individual can at least hope to have some control over that part of the world which is in the future; but the past only acts on her, she can never act back upon it. If she thinks of the world [whether that “world” consists of her life, or human history] as consisting of mostly future, proportionately speaking, she will see herself as fairly free to choose her own destiny and exert her will upon the world. But if her world-view places most of the world in the past, that puts her in a position of powerlessness: not only is she unable to act upon or create most of world in which she exists, but what future does remain is already largely predetermined by the effects of events past.

Who, then, would want to be a meaningless fleck near the end of the eight thousand year history of human civilization? Conceiving of the world in such a way can only result in feelings of futility and predetermination. We must think of the world differently to escape this trap—we must instead place our selves and our present day existence where they rightfully belong, in the center of our universe, and shake off the dead weight of the past. Time may well extend before and behind us infinitely, but that is not how we experience the world, and that is not how we must visualize it either, if we want to find any meaning in it. If we dare to throw ourselves into the unknown and unpredictable, to continually seek out situations that force us to be in the present moment, we can break free of the feelings of inevitability and inertia that constrain our lives—and, in those instants, step outside of history.

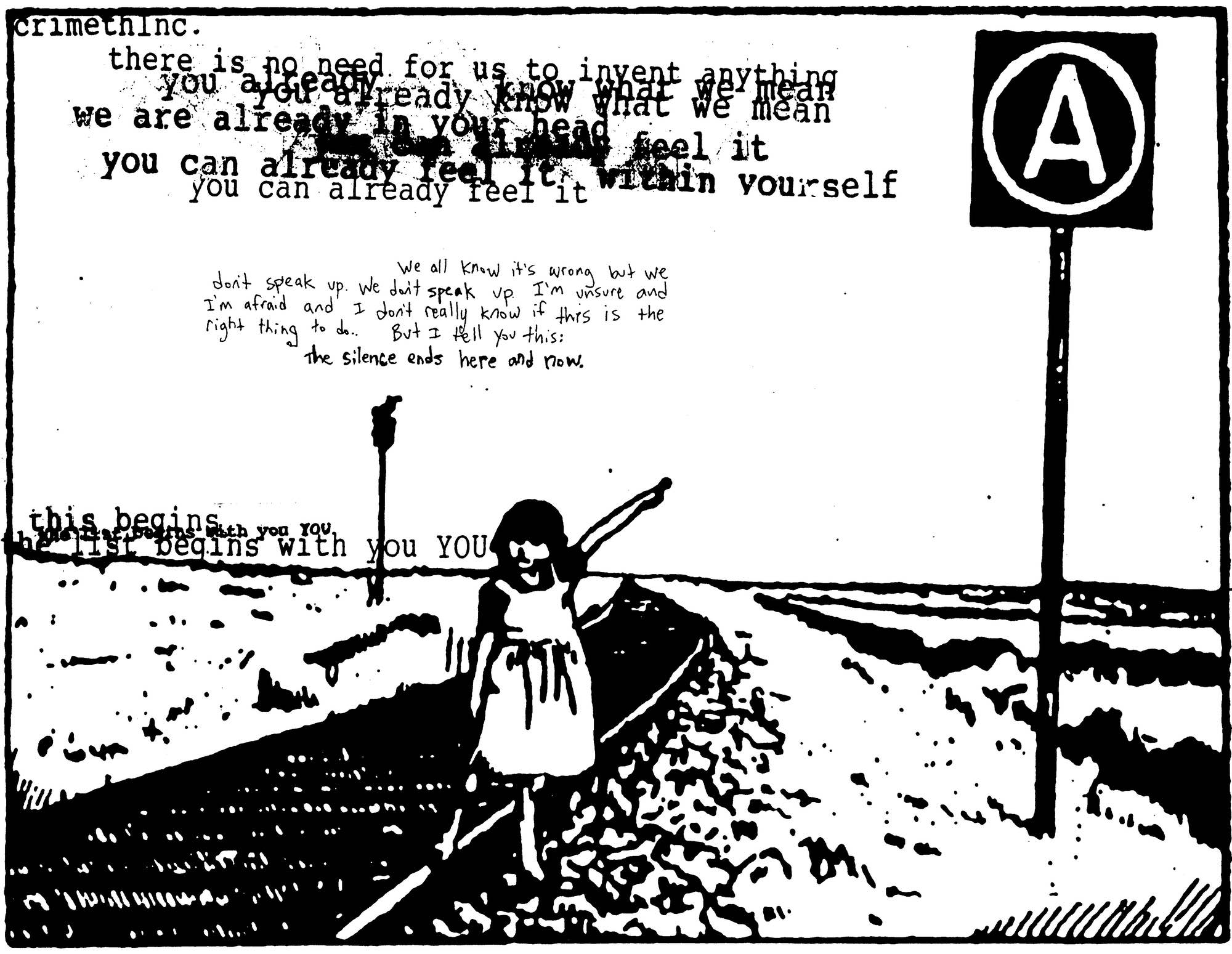

What does it mean to step outside of history? It means, simply, to step into the present, to step into yourself. Time is compressed to the moment, space is concentrated to one point, and the unprecedented density of life is exhilarating. The rupture that occurs when you shake off everything that has come before is not just a break with the past—you are ripping yourself out of the past-future continuum you had built, hurling yourself into a vacuum where anything can happen and you are forced to remake yourself according to a new design. It is a sensation as terrifying as it is liberating, and nothing false or superfluous can survive it. Without such purges, life becomes so choked up with the dead and dry that it is nearly unlivable—as it is for us, today.

None of this is to say that we should condone the deliberate lies of those who would rewrite history, with the intention of trapping us even deeper in ignorance and passivity than we are now. But the solution is not to combat their supposed “objective truths” with more claims to Historical Truth—for it is not more past we need, to weigh upon us, but more attention to today. We must not allow them to make our lives and thoughts revolve only around what has been; instead we must realize that it is up to us to reveal what is true about the present and what is possible from here.

So what can we embrace in place of History? Myth, perhaps. Not the obscurist superstitions and holy lies of religion and capitalism, but the democratic myths of storytellers. Myth makes no claims to false impartiality or objective Truth, it does not purport to offer an exhaustive explanation of the cosmos. Myth belongs to everyone, as it is made and remade by everyone, so it can never be used by one group to lord itself over another. And it does not paralyze—instead of trapping people in the chains of cause and effect, myth makes them conscious of the enormous range of possibilities that their own lives have to offer; instead of making them feel hopelessly small in a vast and uncaring universe, it centers the world again on their own experiences and ambitions as represented by those of others. When we tell tales around the fire at night of heroes and heroines, of other struggles and adventures and societies, we are offering each other examples of just how much living is possible. There may be those who will threaten that the whole world will unravel if we stop concerning ourselves with the past and think only of the present. Let it unravel, then! A lot of good history has done us until now, repeating and repeating itself. Let’s break out of it once and for all, before we too tread the circular path that our ancestors have worn so bare. Let’s make the leap out of History, and make the moments of our daily lives the world we live in and care about—only then can we make it into a place that has meaning for us. The present belongs to those who are able to seize it, to recognize all that it is and can be!

— by Nadia C.