June 2013 saw the biggest wave of protest in Brazil’s recent history. Last month, we published a report from participants in this struggle, which began with demonstrations against a transit fare hike and quickly escalated into countrywide clashes. This is our second installment on the uprising, authored by another group, who offer a more critical perspective on the events.

The June 2013 Uprisings in Brazil, Part II — Giants and Monsters

It isn’t easy to write about the demonstrations in Brazil that began in June 2013. Any attempt at analysis evaporated as the context changed dramatically from one day to the next. What began as a struggle for the reduction of the public transit fare hike became an outcry against police brutality. Then, after huge numbers of people joined the protests in the streets, the message dissolved into a fog of abstractions. When the corporate media realized how serious the threat of violence and property damage was, given the size and intensity of the demonstrations, they did an about-face, supporting the protesters and criticizing the violence of the police. Political figures, artists, and intellectual partisans of the status quo changed their tune, arguing that the demonstrations were legitimate, a fundamental “democratic right,” and represented the will of “all.” Finally, after a historic victory, the fare increase was repealed in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Belo Horizonte, and over a dozen other major cities.

Let’s stop a moment to reflect on where we are, where we are going, and what the risks are.

In São Paulo, the first demonstration was on June 2, and the fare increase was revoked on June 19, after six demonstrations. There were days of massive clashes and police repression like no one had seen in Brazil for a long time. The mobilization reached its peak on June 20 when protesters took the streets in more than 100 cities with great anger against police violence, carrying out attacks on state property, the media, and corporations.

Rio de Janeiro, June 18

Itamaraty Palace attacked in Brasilia

The National Context of the First Demonstrations

The first protests against the fare hikes occurred in Pôrto Alegre in southern Brazil. In March 2013, protesters took the streets and blocked the bus ticket increase. In May, protests in Goiânia accomplished the same thing. However, the cost of not increasing the fares was imposed on taxpayers, not company profits.

The city government of São Paulo had not increased the rates for two years, but several municipalities had just announced a fare hike. On June 6, this was received, as usual, with protests by autonomous student, worker, and youth organizations mobilizing through the Movimento Passe Livre (MPL: loosely, “Free Pass Movement”) under the banner “If the rate does not drop, São Paulo will stop.” Autonomous MPL cells in other regions of the country called demonstrations for the same day. In São Paulo, about 5000 people attended and the march was violently suppressed by the military police with sound bombs, tear gas, rubber bullets, and the usual brutality. The media described the protests as mere vandalism that necessitated a strong state response. Journalists and intellectuals called the protesters a “generation without direction and without cause,” the “spoiled children of the middle class.” Nothing new so far. Average numbers, and just a little more repression than usual. With tempers rising, a new demonstration was called for the next day, June 7. Another march, more graffiti and burning trash, another police ambush, and even more repression. Police shot rubber bullets randomly and a great deal of gas. The governments of the state and the city of São Paulo claimed they could not engage with “hooliganism” and “all or nothing” demands. The Federal government made a statement condemning the demonstrations and offering to help suppress them if necessary.

The third protest, on June 11, showed the repression could be even worse. The march started at Paulista Avenue with nearly 10,000 people escorted by 400 policemen. When participants attempted to occupy a bus terminal, the police responded again with violence and bombs, rubber bullets, and beatings, injuring dozens and making several arrests. There was resistance, and people destroyed many buses along the streets. About 20 people were arrested at random and accused of property damage; some were charged with gang conspiracy, a serious crime in Brazil. The fines amounted to $10,000 for each individual. The government still insisted that it was impossible to return to the previous transit price.

The lack of dialogue and the repression produced a major mobilization in São Paulo for June 13, supporting the prisoners and denouncing police brutality. The popular response was massive: more than 20,000 people attended events promoted on social networks. It was also the day with the most arrests yet—230 altogether. Most of the arrestees were seized before the march began, just for carrying vinegar to protect themselves from tear gas. Journalists were arrested too. There were many reports of police beating people and even sexually abusing women. Despite everything, the authorities still refused to discuss the increase.

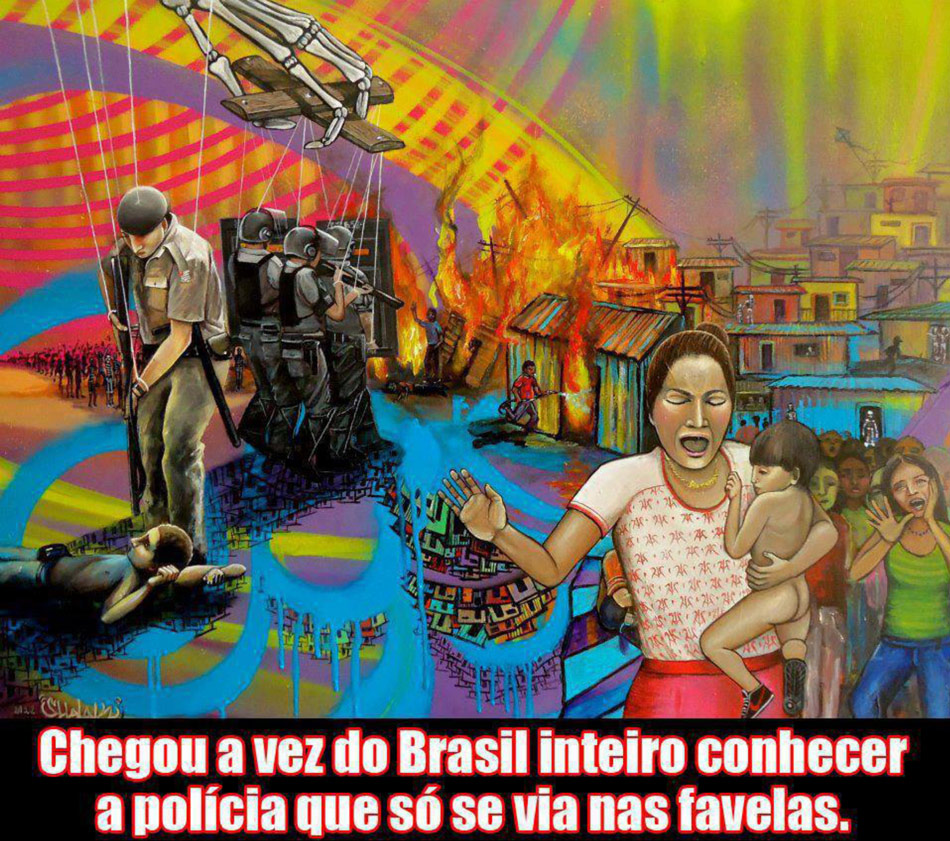

At this point, the media that had been calling the protesters “rebels without a cause” were finally forced to join the wave of criticism against the police, in a shameless attempt at co-optation. The press were embarrassed by the undeniable and disproportionate violence of the military police—who usually perpetrate such violence only in the forgotten streets of the favelas and the countryside, away from others’ eyes and cameras.

“It’s time for the whole country to meet the police only the favelas know.”

Many were injured on June 13, including protesters, passersby, and journalists. Folha de São Paulo, a conservative newspaper accused of morally and financially supporting the repression during the Brazilian military dictatorship, counted seven journalists wounded, including two shot in the face with rubber bullets. Curiously, this paper became the leading voice against police violence, radically changing its speech.

Cell Phones and Cameras as Weapons

In the course of these events, a new factor became decisive. In all of the demonstrations across the country, protesters inspired by the Turkish resistance joined alternative independent media groups using cameras and cell phones to film the police, sharing the footage over the internet live or on the same day. Practically all the clashes were initiated by police, who cornered people chanting “No violence” and fired upon them as they offered no resistance. It became clear that the police were violating their own protocol, which stipulates that they should only use rubber bullets to defend themselves when they are attacked, beginning with warning shots and then aiming below the waist.

Police attacking press with pepper spray

Almost all the videos showed attacks on protesters standing with placards on street corners, people being shot in the face or beaten and arrested, including journalists from the mainstream media and anyone else who filmed police violence. Several images of injured people spread widely via the internet. This had unprecedented repercussions, forcing a shift in the mainstream media narrative to legitimize the marches as an expression of “democracy” and criticize the actions of the police. Journalists and conservative intellectuals apologized and changed their tone about the protests that were gaining support in the streets.

Newspapers changed their approach to the demonstrations; first, they highlighted protester vandalism, then they questioned the brutality of the police.

Reaching Goals, Losing Focus, and the Nationalist Shadow

The fifth demonstration, called by the MPL for Monday, June 17, surprised those who had participated in the movement from the beginning. The momentum had spread across the country. More and more cities joined in, demanding lower prices and better quality in public transport, affirming other local causes including the right to protest itself, and decrying government overspending on infrastructure for the mega-events scheduled over the next few years. In the state of São Paulo, a young man was killed, hit by a driver who could not cross a street during the march.

In the federal capital of Brasilia, thousands took to the streets and around 5000 people surrounded the building of the Senate and Congress, attacking and invading it. The house was empty of political bigwigs, but corporate media filmed everything. This was the first really direct message to the Federal Government.

Crowds surround the Senate and Congress in Brasilia

In Belo Horizonte, in addition to protesting the ticket price, people took to the streets against a ban criminalizing demonstrations that take any public road on the days of the matches of the soccer Confederations Cup; the legislation proposed sentences of up to 30 years for violators. This ban showed that Brazil was yielding to international pressure, especially from the United States, to adopt anti-terrorism laws for upcoming international sports events such as the 2014 Football World Cup and the 2016 Olympics.

In Salvador, Rio de Janeiro, Brasilia, and Cuiaba, the clashes became increasingly violent; some of them occurred on or around the perimeter stipulated by FIFA for the stadiums where the Confederations Cup games were happening. This perimeter is only a preview of what they are planning for the World Cup, with FIFA imposing laws such as the prohibition of demonstrations and informal trade within three kilometers of the stadiums and perhaps even banning the right to strike.

As the clashes intensified, hackers invaded the websites and twitter profiles of government agencies and corporate media, using them to broadcast subversive texts and images of police violence, and inviting people to mobilize and continue the fight for lower fares.

The impact of police violence and the favorable coverage given by the media produced broad popular support, with many new people joining the movement. There were solidarity demonstrations in 27 countries worldwide. The international impact was huge and even the international corporate media strongly criticized the Brazilian police and government.

Yet the adhesion of the middle and upper class to the movement brought side effects. Across the country, people showed up with posters proclaiming phrases taken from Facebook and Twitter, slogans like “The giant awoke,” “It’s not just for 20 cents,” and vague statements against “corruption,” for tax cuts, and of love for a motherland in which people only occupy the streets for football and Carnival.

March against the FIFA in Belo Horiozonte.

Early on the day of the fifth march in São Paulo, announcements appeared on the internet that building materials such as bricks and pieces of iron had appeared overnight at the starting point of the demonstration. In a nearby square, a bus from the city lines was parked in a very unusual place. Many feared this was an ambush, in which potential weapons were provided to incite violence that would be “properly” suppressed by the police. This news made the city hastily gather the materials, but the circus was just beginning.

That day, more than 100,000 people gathered in Largo da Batata, near the Faria Lima Metro Station, one of the newest and most modern stations in the city. The march followed a long, tiring route, escorted by hundreds of police officers. The “masses” in attendance had their faces painted green and yellow (the national colors) or were wrapped in the national flag, with clown noses, singing hymns and chanting their generic demands. The giant had woken up, but it had no idea what to do.

It was necessary to focus in order to stop the increase in fares. The protesters were permitted to tramp the sacred ground of Paulista Avenue because, according the police, they deserved it for good behavior. However, dissidents marched to the Bandeirantes Palace, seat of State Government. The building was surrounded and forced open, so the police had to attack the protesters from inside the building to disperse the demonstration. The day concluded with great frustration about the loss of focus and the nationalism invading the movement.

But about two hours earlier, in Rio de Janeiro, the protests had radicalized when a crowd attacked the State Legislature, using sticks, stones, fireworks, and Molotov cocktails to corner 70 policemen inside the building. Cars were burned, 20 police officers were injured, and the building was destroyed with losses of more than a million dollars. The people of Rio de Janeiro showed that the participation of the masses could be overwhelming for the authorities as well as for the original protesters. Trapped, the police used live ammunition, shooting seven people. Other cities, such as Porto Alegre and Belo Horizonte, also got in the news for confrontations, but in those cases police violence was the main story. In all the events from June 17 on, the media began to adopt specific language about the protest that was repeated on every network. In headline after headline and report after report, it was necessary to emphasize that a “minority” was responsible for the acts of violence and destruction, while the “vast majority” consisted of peaceful protesters that fit the profile required by a “democratic system.” Later, the minority became thugs, radicals, extremists, and even bandits and dangerous criminals. This was the same minority that had initiated the movement in the first place!

The sixth demonstration, on June 18, was the last one before the rate increase was repealed; it also put new questions to the movement. The advocates of pacifism that had brought in a pride in citizenship and the desire to “preserve the public good” denounced and even personally attacked those writing graffiti and committing acts of “vandalism.” That day, the Military Police disappeared from the streets of Sao Paulo. More than 100,000 protesters marched through the center again and down Paulista Avenue. But some people from the “minority that spoils the movement” walked downtown and arrived at City Hall without difficulty. Anyone who has witnessed demonstrations in front of that building before knows it is almost untouchable and always guarded by the forces of the Military Police (which is administered by the state government) and the Municipal Guard.

That day, the MP was not there to protect the building; its cabin located on the same corner as the City Hall was empty. In a suspicious turn of events, the way was open for the crowd. Probably the Military Police, ruled by the right-wing State Government, wanted to see the Mayor in the same danger they had faced the previous night. The result was that the City Hall was surrounded; the Municipal Guard was cornered and forced to enter the building. Its front door was smashed and decorated with graffiti. The gatehouse of the MP was destroyed and burned. A television van was torched. The streets of downtown were unprotected against the newly released anger of the people. Dozens of shops were looted by “a few thugs.” The next day, June 19, the rate increase was rescinded.

100 Cities Take the Streets—and with Them, 100 Million New Policemen

When he finally understood the scale of popular pressure, Mayor Fernando Haddad met with the bigwigs of his party, the PT (Workers Party), including former president Lula, president Dilma, and some marketing managers concerned with his image. The Mayor changed his tone, announcing in meetings with the MPL and in public statements that it was possible not to increase the price of tickets but it was not yet possible to predict when this could be formalized. The morning after the attack on City Hall, he announced that there would be no increase anymore.

This map shows the locations and sizes of demonstrations. The largest had more than 300,000 participants.

The seventh day of action became a celebration day in Sao Paulo. Over 100 cities around the country also hosted demonstrations and clashes. In Brasilia, the Palace of the Foreign Ministry, the headquarters of international relations, was surrounded with the president and ministers trapped inside. The entrance hall of the building was invaded and attacked as a crowd of over 10,000 protesters throwing rocks and Molotov cocktails took the unprepared building security by surprise. It was estimated that nearly 2 million people took to the streets nationwide. Yet the climate of optimism was fading in many places.

In Porto Alegre, the scene of some of the most violent conflicts with the Military Police, the anarchist group Federação Anarquista Gaúcha (FAG) had its headquarters invaded by police. About 15 ununiformed policemen wearing only vests, said to be the Federal Police, raided the place without presenting any warrant, seizing materials such as books and paint in an attempt to incriminate the group for vandalism. The “minorities” that cause destruction and “come into confrontation” with police must be identified and isolated from the “good citizens” who occupy the streets “democratically.” Again, several protesters were grabbed and handed over to the police by other protesters for painting graffiti, attacking buildings and banks, or even simply covering their faces. It seemed to be the beginning of a nationwide manhunt.

Anarchist presence in a march in Porto Alegre to halt rising transportation costs.

Brazil is a Pressure Cooker

The celebratory demonstration in Sao Paulo revealed something even worse than nationalism. In his move to restore the image of the PT, Mayor Haddad invited all members and supporters to occupy the streets dressed in red and with their flags to celebrate the victory of the people; he called this the “Red Wave.” Right-wing groups, claiming to be “anti-party,” tried to use the nonpartisan tone of the demonstrations to take advantage of the stupidity of thousands of uncritical protesters to call for open season on Left parties, black and gay movements, and other political minorities. An anarchist group marching nonviolently in black with a red and black flag was booed by protesters who opposed the party flags, confirming their ignorance of everything that was going on: they thought the anarchists were a party.

Several clashes exploded between protesters for and against the presence of parties, creating a tense atmosphere on Paulista Avenue. At the same time, in the building of FIESP (Federation of Industries of the State), military officials and politicians were discussing new directions for the defense industry.

The bright panels of the building showed a giant flag of Brazil, and the chants against political parties had no libertarian spirit. In this nationalist atmosphere, the protest was directed against the current mayor and the president of Brazil, as representatives of the PT.

It was the first time since its foundation that this party had been thrown out of a mass demonstration by the people itself. Society has changed and they have failed to extend their connections to the newer generations, remaining tied only to some older movements like the MST (Landless Workers Movement). The right wing hoped to take advantage of this situation. These right-wing politicians run the state of Sao Paulo with Geraldo Alckimin (PSDB)—the same government that controls the Military Police that withdrew so City Hall could be attacked one night before. In this fog of vague ideas and nationalist sentiments, it’s hard to know who is who, what they want, and how they pursue their goals.

This moment served the elite in their agenda to recapture the presidency of the republic and intensify the repression of popular social movements. The climate of tension and uncertainty remained. There were rumors on the streets and the internet about a new military coup. The United States exchanged its ambassador in Brazil with the one that was in Paraguay during the military coup in 2012. The MPL announced the end of demonstrations after its goals have been achieved, warning that the fight would continue in other ways and it was not useful to insist on unfocused demonstrations now that its original goals had been met.

Meanwhile, on the border of Sao Paulo and in many other cities, less privileged people rose to demand their rights by closing roads. In the northern zone of São Paulo, a policeman was shot and three protesters were killed—a more serious toll than at any national demonstration for two weeks. The lives of those in the favelas who are not white or middle class are very distant from the reality people experience in the city center. The police treat resistance in the favelas differently; they occupy these areas nonstop, readily employing brutal force far from the eyes of public opinion.

Other demonstrations were called by autonomous, nonpartisan groups hoping to maintain popular pressure around many other issues pending in Brazil. The country is a pressure cooker; the wave of demonstrations in June was just a tiny bit of steam escaping. In Rio de Janeiro on June 24, people from a favela called Mare demonstrated; in response they suffered a military incursion by the BOPE (a murderer elite police troop), who killed 13 people. Instead of rubber bullets, only real ones were fired.

“Vandal” arrested by other protesters in Vitoria, Espirito Santo.

The Means Must Justify Itself Now: This Fight Has No End

In Brazil, there are countless reasons to protest. Allegations of torture against protesters have been reported in Salvador and other cities. The evangelical lobby is pressing Congress to approve psychological treatment for homosexuality and ban abortion in cases of rape—a tremendous setback for a right that women already possess only in cases of sexual violence. Anti-terrorism laws are to be voted in under US pressure to criminalize demonstrations that block the street or cause property damage. MST activists and MTST activists (the Homeless Movement) are persecuted and arbitrarily arrested. UN representatives are asking Brazil to end the Military Police, and popular groups are organizing to support this. Research shows that Brazil already has about 5000 unregulated drones flying; the BOPE and landowners are testing this technology. FIFA continues to press Brazil for more security for business during next year’s World Cup. Evictions continue everywhere in order to modernize the cityscape and build roads, airports, and structures for the upcoming mega-events. In indigenous territories, there are battles to make way for dams and power stations and secure the advancement of agri-business. The demarcation of indigenous lands is no longer the responsibility of FUNAI (National Indian Foundation) but now the EMBRAPA (Brazilian Agricultural and Livestock Research).

Popular committees bringing together communities, students, and unions are forming in Belo Horizonte and elsewhere to discuss the next direction for popular demands. The fight is far from over. Now the people of Brazil have a new action profile in their résumé—for good or for ill. There is a lot to discuss about how to maintain a struggle without being contaminated by middle-class patriotism imported from football and Carnival, and how to face the elites who are determined to destroy or coopt the general discontent. Now the State and the Police also know what can happen when people come out to the streets; they will be careful not to make the same mistakes again. The fight is becoming increasingly harsh; new obstacles appear everywhere we have succeeded in taking a step forward. Anarchists and radicals, who have remained outside the spotlight of the media and police until now, will be persecuted as before, along with other “inciters of violence and vandalism.” Many already face charges.

We need a new security culture to protect individuals and groups mobilizing in social struggle, new ways of defending and attacking without taking too many risks. We need to discuss diversity of tactics, considering that our militarized police force is comparable to those in countries under dictatorship or foreign occupation, prepared to kill without any dialogue. According to Amnesty International, in the favelas and in the countryside, it is the biggest killer on the planet.

At the same time, we need to make what we are doing as horizontal, autonomous, liberating, and pleasurable as possible, because the end does not seem to be even visible on the horizon. The means will be all we have for a long time.