Adapted from George Orwell’s Homage to Catatonia.

Does your father drift from one hobby to another, fruitlessly seeking a meaningful way to spend the little “leisure time” he gets off from work? Does your mother endlessly redecorate the house, going from one room to the next until she can start over at the beginning again? Do you agonize constantly over your future, as if there was some kind of track laid out ahead you—and the world would end if you turned off of it? If the answer to these questions is yes, it sounds like you’re in the clutches of the bourgeoisie, the last barbarians on earth.

The Martial Law of Public Opinion

Public opinion is an absolute value to the bourgeois man and woman because they know they are living in a herd: a herd of scared animals, that will turn on anyone it doesn’t recognize as its own. They shiver in fear as they ponder what “the neighbors” will think of their son’s new hairstyle. They plot ways to seem even more normal than their friends and coworkers. They don’t dare fail to turn on their lawn sprinklers or dress appropriately for “casual Fridays” at the office. Anything that could drag them out of their routines is viewed as suspect at best. Love and lust are both diseases, possibly fatal, as are all the other passions that could drive one to do things that would result in expulsion from the flock. Keep them quarantined to secret affairs and teenage dates, to night clubs and strip clubs—for God’s sake, don’t contaminate the rest of us. Go wild when “your” football team wins a game, drink yourself into oblivion when the weekend comes, rent obscene movies if you have to, but don’t you dare sing or run or make love out here. Under no circumstances admit to feeling anything that doesn’t belong in the staff room or at the dinner party. Under no conditions admit to wanting anything more or different than what “everyone else” wants, whatever and whoever that might be.

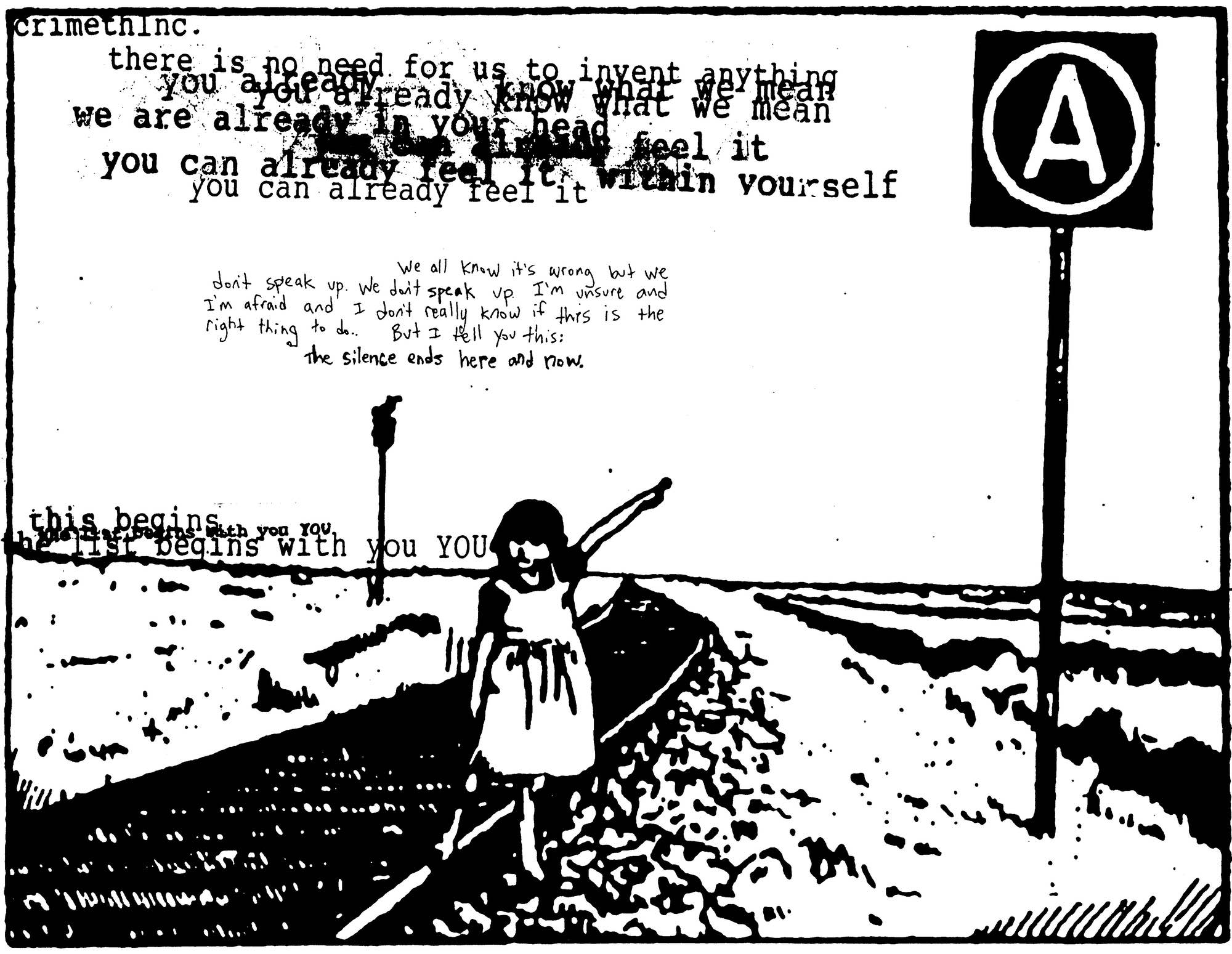

And of course their children have learned this, too. Even after the death matches of the grade school nightmare, even among the most rebellious and radical of the nonconformists, the same rules are in place: don’t confuse anybody as to where you stand. Don’t use the wrong signifiers or subscribe to the wrong codes. Don’t dance when you’re supposed to be posing, don’t speak when you’re supposed to be dancing, don’t mess with the genre or the moves. Make sure you have enough money to participate in the various rituals. To keep your identity intact, make it clear which subcultures and styles you’re aligned to, which bands and fashions and politics you want to be associated with. You wouldn’t dare risk your identity, would you? That’s your character armor, your only protection against certain death at the hands of your friends. Without an identity, without borders to define the edges of your self, you’d just dissolve into the void… wouldn’t you?

The Generation Gap

The older generations of the bourgeoisie have nothing to offer the younger ones because they have nothing in the first place. All their standards are hollow, all of their riches are consolation prizes, not one of their values contains any reference to real joy or fulfillment. Their children sense this, and rebel accordingly, whenever they can get away with it. The ones that don’t have already been beaten into terrified submission.

So how has bourgeois society continued to perpetuate itself through so many generations? By absorbing this rebellion as a part of the natural life cycle. Because every child rebels as soon as she is old enough to have a sense of self at all, this rebellion is presented as an integral part of adolescence—and thus the woman who wants to continue her rebellion into adulthood is made to feel that she is insisting on remaining a child forever. It’s worth pointing out that a brief survey of other cultures and peoples will reveal that this “adolescent rebellion” is not inevitable or “natural.”

This perpetual rebellion of the youth also creates deep gulfs between different generations of the bourgeoisie, which play a crucial role in maintaining the existence of the bourgeoisie as such. Because the adults always seem to be the enforcers of the status quo, and the youth do not have the perspective yet to see that their rebellion has also been absorbed into that status quo, generation after generation of young people are able to make the mistake of identifying older people themselves as the source of their misfortunes rather than realizing that these misfortunes are the result of a larger system of misery. They grow older and become bourgeois adults themselves, unable to recognize that they are merely replacing their former enemies, and still unable to bridge the so-called generation gap to learn from people of other age groups… let alone establish some kind of unified resistance with them. Thus the different generations of the bourgeoisie, while seemingly fighting amongst themselves, work together harmoniously as components of the larger social machine to ensure maximum alienation for all.

The Myth of the Mainstream

The bourgeois man depends upon the existence of a mythical mainstream to justify his way of life. He needs this mainstream because his social instincts are skewed in the same way his conception of democracy is: he thinks that whatever the majority is, wants, does, must be right. Nothing could be more terrifying to him than this new development, which he is beginning to sense today: that there no longer is a majority, if there ever was.

Our society is so fragmented, so diverse, that at this point it is absurd to speak of a “mainstream.” This is a myth partly created by the anonymity of our cities. Almost everyone one passes on the street is a stranger: one mentally relegates these anonymous figures to the faceless mass one calls the mainstream, to which one attributes whatever properties one thinks of strangers as possessing (for the smug salesman, they all envy him for being even more respectable than they are; for the insecure bohemian rebel, they must disapprove of him for not being like they all are). They must be part of the silent majority, that invisible force that makes everything the way it is; one assumes that they are the same “normal people” seen in television commercials. But the fact is, of course, that those commercials refer to an unattainable ideal, in order to keep everyone feeling left out and insufficient. The “mainstream” is analogous to this ideal, as it keeps everyone in line without ever actually making an appearance, and possesses the same degree of reality as the perfect family in the toothpaste advertisement.

No one worries more about this absent mass than the bohemian children of the bourgeoisie. They bicker over how to orchestrate their protests to gain “mass appeal” for their radical ideas, as if there still was a mass to appeal to! Their society is now made up of many communities, and the only question is which communities they should approach… and dressing “nice,” proper language and all, is probably not the best way to appeal to the most potentially revolutionary elements of their society. In the last analysis, the so-called “mainstream” audience most of them imagine they are dressing up for at their demonstrations and political events is probably just the specter of their bourgeois parents, engraved deep in their collective subconscious as a symbol of the adolescent insecurity and guilt they never got over. They would do better to cut their ties to the bourgeoisie entirely by feeling free to act, look, and speak in whatever ways are pleasurable, no matter who is watching—even when they are trying to advance some political cause: for no political objective reached by activists in camouflage could be more important than beginning the struggle towards a world in which people will not have to disguise themselves to be taken seriously.

This is not to pardon those insecure bohemians who use their activism not as a means of building ties with others, but rather as a way to set themselves apart: in their desperation to purchase an identity for themselves, they believe they must pay for it by defining themselves against others. You can recognize them by their self-righteousness, their pompous show of ideological certainty, the ostentatious way they declare themselves “activists” at every opportunity. Political “activism” is almost exclusively their sphere, today, and “exclusive” is the key word… until this changes, the world will not.

Marriage… and Other Substitutes for Love and Community

Reproduction is a big issue for the bourgeois man and woman. They can only have children under very precise circumstances; anything else is “irresponsible,” “unwise,” “a poor decision for the future.” They must be prepared to give up every last vestige of their youthful, selfish freedom to have children, for the mobility their corporations demand and the strain of vicious competition have destroyed the community network that long ago used to share the labor of child-rearing. Now every family unit is a tiny military outpost, closed and locked to the outside world both in their hearts and in the paranoia-turned-city-planning of their suburbs, each one an isolated emotional economy to itself where scarcity is the key word. The father and mother must abandon their selves for the prescribed roles of care-giver and bread-winner, for in the bourgeois world there is no other way to provide for the child. Thus the bourgeois couple’s own fertility has been made a threat to their freedom, and a natural part of human life has become a social control mechanism.

Marriage and the “nuclear family” (the atomized family?) as chain gang have survived as a result of this calamity, much to the misfortune of potential lovers everywhere. For as the young adventurer, who keeps her lusts strong and her appetite whetted with constant danger and solitude, knows well, love and sexual desire cannot survive overexposure—especially in the dull and lifeless settings that most married partners share time. The bourgeois husband sees the only lover he is permitted under only the worst possible circumstances: after every other force in his world has had the chance to exhaust and infuriate him for the day. The bourgeois wife learns to punish and ignore as “unrealistic” and “impractical” her every desire for romance, spontaneity, wonder. Together, they live in a hell of unfulfillment. What they need is a real community of caring people around them, so parenthood would not force them into unwanted “respectability,” so they would still be free to have the individual adventures they need to keep their time together sweet, so they would never find themselves so lost and desperately lonely.

In just the same way, their steady supply of food, of conveniences, comforts, and diversions avail them not. For as every hitchhiker, every hero, every terrorist knows, these things gain their value through their absence, and can offer real joy only as luxuries happened upon in the pursuit of something greater. Constant access to sex, food, warmth, and shelter desensitize a man to the very pleasures they afford. The bourgeois man has given up his chance to pursue real stakes in life for the assurance that he will have these amenities and securities; but without real stakes in his life, these can offer him no more real joy than the company of his fellow prisoners.

The Joys of Surrogate Living!

You can take a quick tour of all the unacted desires of the bourgeois man just by turning on his television or stepping into one of his movie theaters. He spends as much of his time as he can in these various virtual realities because he instinctively feels that they can offer him more excitement and satisfaction than the real world. The saddest part is that, so long as he remains bourgeois, this may actually be true. And as long as he accepts the displacement of his desires into the marketplace by paying for imitations of their fulfillment, he will be trapped in the empty role that is himself.

These desires are not always pretty to see played out in Technicolor and SurroundSound: the bourgeois man’s dreams and appetites are as infected by the fetishization of power and control as his society is. The closest he seems to be able to offer to an expression of free, liberated desire is the fantasy of all-consuming destruction that appears again and again at the black heart of his wildest cinematic fever dreams. This makes sense enough—after all, in a world of nothing but strip malls and theme parks, what honest thing is there to do but destroy?

The bourgeois man is not equipped to view his desires as anything but unfortunate weaknesses to be fended off with placebos because his life has never been about the pursuit of pleasure—he has spent several centuries achieving higher and higher standards of survival at the cost of everything else. Tonight he sits in his living room surrounded by computers, can openers, radar detectors, home entertainment systems, novelty ties, microwave dinners, and cellular phones, with no idea what went wrong.

The bourgeois man is only possible by virtue of the blinders he wears that prevent him from imagining that any other way of life is possible. As far as he can tell, everyone from the impoverished migrant workers of his own nation to the monks of Tibet would be bourgeois too, if only they could afford it. He does his damnedest to maintain these illusions; without them, he would have to face the fact that he has thrown his life away for nothing.

The bourgeois man is not an individual. He is not a real person (although if he was, he would probably live in Connecticut). He is a cancer inside all of us. He can now be cured.